Aquí Estamos: The Zoot Suit Legacy and the Power of Mexican American Representation at The Petersen Automotive Museum

Zoot suits and lowrider culture are not just aesthetics—they are symbols of resistance, culture, and survival. The zoot suit is more than fabric stitched together; it’s a statement, a rebellion, a legacy that has endured despite racism, erasure, and every attempt to diminish the contributions of Mexican Americans to fashion, history, and the shaping of Los Angeles itself. Just as lowriders cruise the streets as rolling testaments to Chicano innovation and pride, zoot suits continue to stand as a bold declaration of identity, defiance, and cultural perseverance.

Draped in a stunning dress from Vintage Vandalizm (Latina-owned), paired with Bianca Luck shoes (Latina-owned), and makeup by Bésame Cosmetics (Latina-owned) and Adriana Nichole Cosmetics (Black woman-owned).

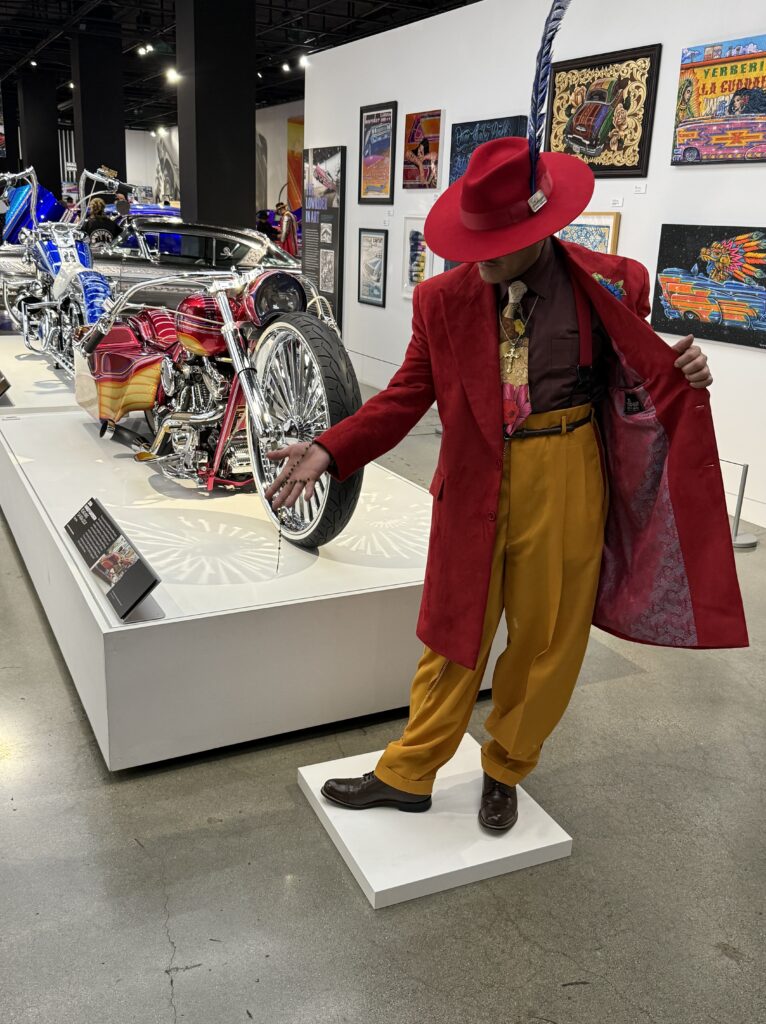

At the Petersen Automotive Museum, where the steel and chrome of vintage lowriders reflected the deep reds of the evening’s runway, our history stood bold and unapologetic. The El Pachuco Zoot Suit fashion show, led by the powerhouse that is Vanessa Estrella, wasn’t just a presentation of garments—it was a reminder. Aquí estamos.

Why the Zoot Suit Matters: More Than Fashion, It’s Defiance

The zoot suit is American history—but it’s a history that has been buried, rewritten, and ignored in mainstream narratives.

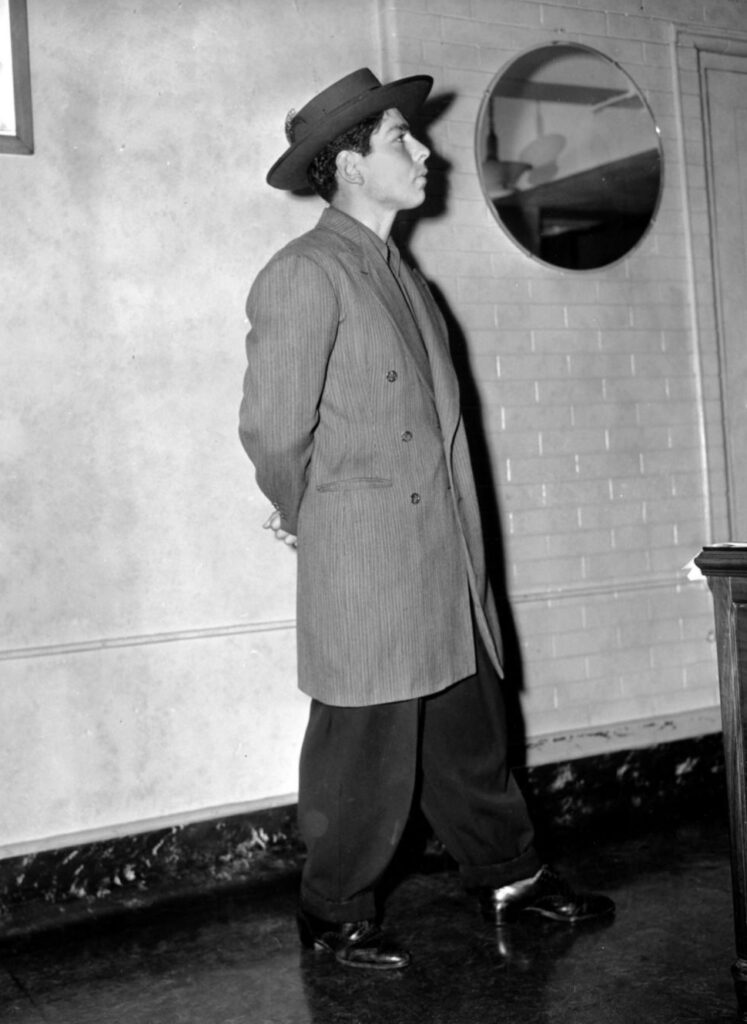

It’s a history that belongs to the Mexican American youth of the 1940s who dared to be loud, proud, and visible in a society that wanted them to shrink. It belongs to the Black jazz scene of the 1930s that birthed the style, and to the pachucos and pachucas who carried it into the heart of Chicano identity.

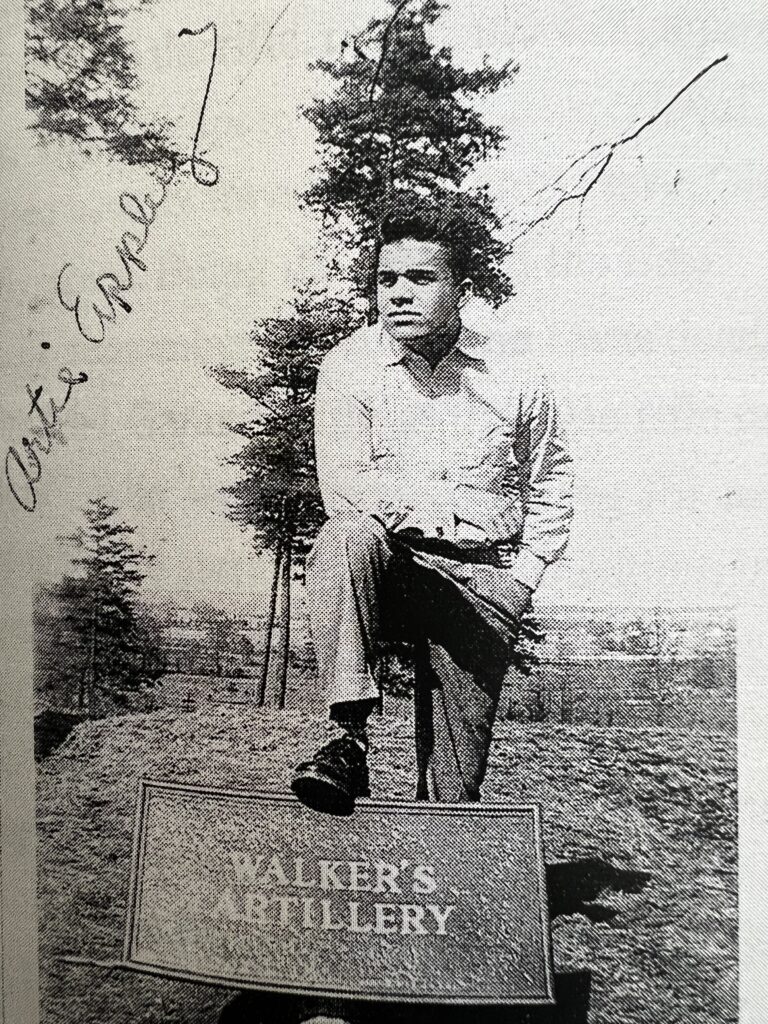

For me, this history is more than just something I write about—it’s in my blood. My great uncle, Art Eppley, was a pachuco in Los Angeles in the 1940s. He didn’t just live through this era—he documented it, writing about his experiences, capturing a world that was alive with music, defiance, and community. He literally wrote out his entire life story and it’s incredible.

Like many young pachucos, he wasn’t just defined by the suit—he carried that same discipline, confidence, and resilience into the rest of his life. He would go on to thrive as a Colonel in the Marine Corps, proof that being pachuco wasn’t about delinquency, as the newspapers claimed—it was about strength, about identity, about knowing exactly who you are.

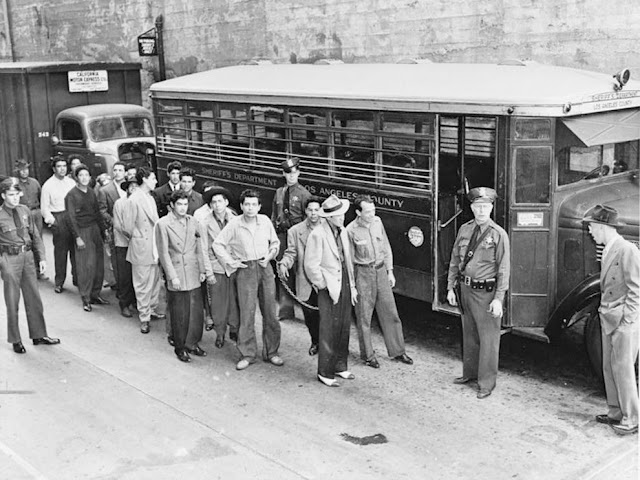

The Zoot Suit Riots of 1943 were never really about fashion.

They were about power—about white servicemen attacking young Mexican Americans simply because they were bold enough to take up space, to wear suits that defied assimilation, to exist outside of what mainstream America deemed acceptable.

The newspapers at the time painted the wearers as criminals, delinquents, dangerous. But what they really were was free.

And that’s why seeing those suits walk down the runway in 2025 is revolutionary. For me, it’s deeply personal—because every step those models took, every swing of a chain, every tilt of a fedora wasn’t just a tribute to history—it was a tribute to my family, my culture, and the legacy that I carry forward as both a journalist and in my everyday life.

Zoot Suits Take Center Stage: A Fashion Show Rooted in History

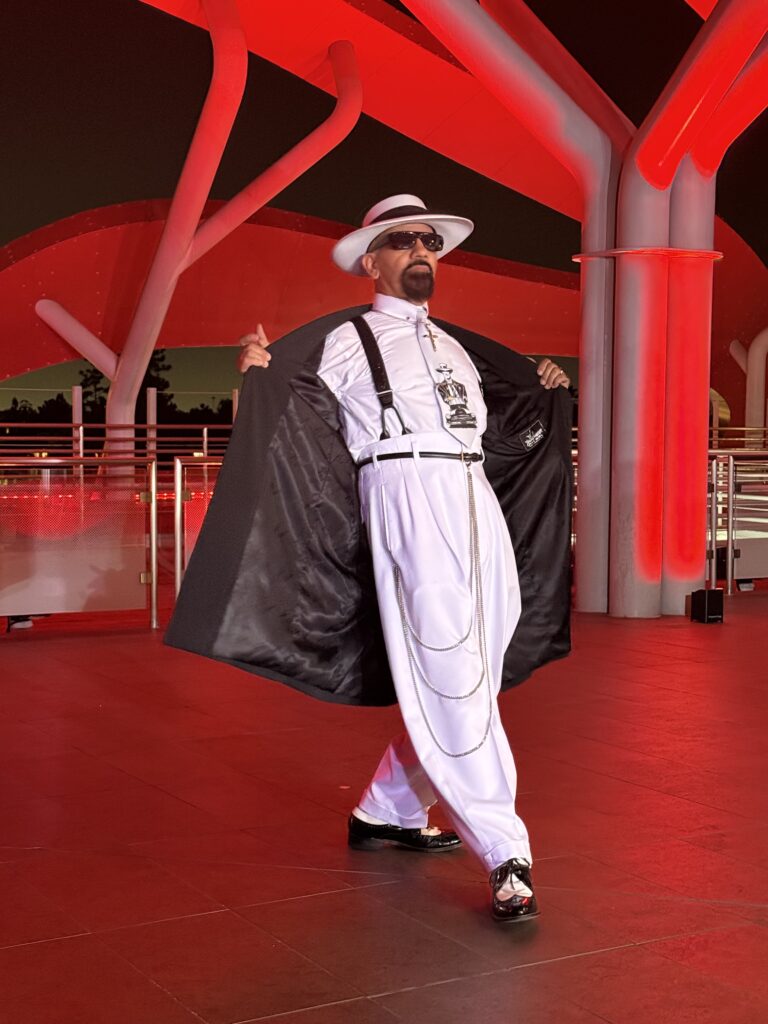

Under the electric red glow of the Petersen Automotive Museum’s futuristic architecture, models took to the runway, embodying the essence of pachuco and pachuca culture—each step, each stance, each tilt of a fedora a powerful reminder that this legacy is still alive and thriving.

The music? Lalo Guerrero’s Los Chucos Suaves spilled from the speakers, its infectious rhythm setting the stage for a night of sartorial defiance. Each model glided across the floor, exuding the effortless cool that defined the zoot suit era. This wasn’t just a fashion show; it was a resurrection of history, a celebration of identity, and a refusal to be erased.

The Most Powerful Moments of the Night:

A young girl strutting in her custom zoot suit, hands in her pockets, stance wide and confident—proof that this legacy is alive and well in the next generation. The swing of her chain, the sharp pleats of her trousers, and the way she awore her pachuca pompadour just so—it all told a story. A story of tradition, of empowerment, of resilience.

A model in white and dark brown, gripping his lapels with pride, his hat perfectly matching the entire ensemble. The weight of a long, heavy chain swung from his waist, accentuating every step, an unspoken nod to the rebellious pachucos of the 1940s, who wore their extravagant suits in the face of hostility and prejudice.

A sharp-dressed woman in a perfectly tailored rich burgundy plaid zoot suit, her suspenders adding just the right amount of tension to her stance. The interplay of bold textures—crisp wool, rich satin linings, and heavy drapes—made it clear: the pachuca aesthetic is not a relic of the past. It’s here. It’s now. It’s a statement.

A musician in a striking green coat, playing the trumpet, her vibrant purple hair adorned with flowers as bold as her suit. The fusion of music and fashion was undeniable—a seamless blend of the big-band jazz era and the enduring spirit of Chicano culture. As the brass wailed, the models moved to the rhythm, their zoot suits swaying in time with the music—a perfect harmony of fashion and culture.

A hauntingly beautiful calavera-painted model, standing in silence, his crimson suit gleaming under the lights. A chilling yet powerful tribute, he served as a reminder that our ancestors are always with us, guiding us, celebrating our survival. In a world that tried to erase Mexican American culture, the zoot suit has endured—just as we have.

Vanessa Estrella, radiant in a stunning pink pachuca suit, stole the show—not just on the runway, but outside, where she posed next to the legendary Gypsy Rose lowrider, the iconic pink 1964 Chevy Impala. The parallel was striking: both Vanessa and the Gypsy Rose embodied the same ethos—bold, beautiful, and unapologetically Chicana. Her outfit wasn’t just a fashion statement; it was a deliberate nod to the culture that shaped this movement, an assertion that women have always been an integral part of this history, from the streets to the car clubs to the runways.

One of the most visually stunning and deeply significant moments of the night came from a model draped in a zoot coat adorned with the image of the Virgen de Guadalupe. A towering figure in the show, he commanded the runway with reverence, a massive feather tucked into his hat and a rosary clutched in his hands. The Virgen de Guadalupe is more than just a religious symbol—she represents the strength and resilience of Mexican people, a beacon of faith and protection in times of struggle.

His presence was a reminder that pachuco culture is not just about fashion—it is about identity, spirituality, and the unbreakable ties that bind us to our ancestors. The rich embroidery of his coat gleamed under the lights, matching the deep hues of a meticulously customized lowrider parked outside, reinforcing the connection between Chicano fashion, car culture, and faith.

Vanessa’s opening speech, declaring to the crowd: “Aquí estamos.” Here we are. A proclamation that needed no embellishment. These suits, these faces, this moment—it was proof that pachuco culture never died. It lives in every thread of these tailored masterpieces, in every glide across the floor, in every knowing nod exchanged between generations.

But the energy of the night didn’t stop at the runway. Outside, history rumbled to life on four wheels.

The Art of the Strut: The El Pachuco Stance Lives On

It wasn’t just the fashion that made the night electric—it was the attitude.

From the exaggerated tilts of wide-brimmed fedoras to the slow, deliberate way models strutted and glided across the runway, this show honored a movement rooted in both defiance and artistry. The stance, the walk, the pose—it was the El Pachuco stance, immortalized by Edward James Olmos in Zoot Suit (1981).

Olmos’s portrayal of El Pachuco in Luis Valdez’s groundbreaking musical was hypnotic and seductive, turning the hep-cat stance into an emblem of defiance. The way a pachuco moves—smooth, cool, never rushed—is just as important as the clothes themselves. It’s about owning space in a world that tried to shrink us.

Zoot Suit is still the most influential play written by a Chicano author—the only one to reach Broadway. And its impact could be felt in every turn, every step, every lapel grip on that runway.

This wasn’t just a fashion show. It was a declaration.

Lowriders and Legacies: The Cars That Tell Our Story

You can’t talk about pachucos without talking about lowriders. They’re two sides of the same coin—art in motion, rebellion on display, a cultural statement that refuses to be ignored.

The Petersen Automotive Museum’s first floor showcase was a living tribute to lowrider culture, with cars that weren’t just vehicles, but rolling pieces of history.

The Legendary Gypsy Rose: The Queen of Lowriders

From cruising Whittier Blvd. in Chico and the Man to its debut at the 1968 Winternationals Custom Show, Gypsy Rose is THE most recognized lowrider in the world. But beyond the candy paint and roses, this ’64 Impala tells a deeper story—one of Chicano pride, resistance, and community. Created by Jesse Valadez, founder of the Imperials Car Club, the hand-painted roses were a tribute to his mother.

At a time when Mexican-American communities faced discrimination, lowriders became rolling statements of identity and power. And today? Lowriding is still multigenerational, still a family affair, still a movement.

Dripping in pink candy paint and intricate rose patterns, Gypsy Rose was a testament to craftsmanship, creativity, and the deep storytelling embedded in lowrider culture. It wasn’t just a car—it was a movement, a symbol that Mexican Americans belong in the mainstream narrative of automotive history.

🎶 “A new day has begun…” 🎶 If you know, you know.

The Peach Lowrider: Women in Lowrider Culture

But it wasn’t just men behind the wheel.

The 1966 Chevy Impala peach-colored lowrider stood out for more than just its warm, shimmering hue—it was a statement that women are just as much a part of lowrider culture as men.

Women have been painters, upholsterers, mechanics, and drivers in the scene for decades, yet their contributions are often overlooked. This car, with its elegant but fierce presence, was a reminder that lowriding is for everyone.

It was a perfect complement to the El Pachuco fashion show, where women strutted in zoot suits, further proving that Mexican American culture has never been a boys’ club.

More Standout Lowriders of the Night

Every car had a story, but a few stood out as undeniable highlights. These were some of my favorite cars:

If there’s one thing the De Alba family knows, it’s how to build a lowrider that turns heads and cements legacies. With three generations in the Pomona lowrider scene, they’ve perfected the craft, and Dead Presidents—a jaw-dropping 1958 Chevy Impala—is no exception. Unveiled in 2023 for Albert De Alba Sr.’s 50th birthday, this masterpiece was two years in the making, boasting shaved door handles, a hand-built grille, fiberglass bodywork, and a completely customized interior. But its real showstopper?

The candy and metal flake paint job in deep green and gold, a testament to Albert Jr.’s skill with a spray gun. A standout at the Lowrider Las Vegas Super Show and the NHRA Motorsports Museum, Dead Presidents isn’t just a car—it’s a rolling tribute to craftsmanship, family, and the relentless innovation of lowrider culture.

Takahiko Izawa’s 1958 Chevy Impala isn’t just a car—it’s a work of art on wheels. Growing up in Japan, Izawa first discovered lowrider culture through the pages of Lowrider Magazine, drawn to the incredible paint jobs that transformed cars into masterpieces.

In a country with its own thriving custom car scene, where attention to detail is everything, lowriders stood out as a unique blend of self-expression and craftsmanship. Inspired by this, Izawa spent 25 years perfecting his technique, determined to create something never seen before.

As President of Rohan Co., Ltd, Izawa didn’t just customize his ’58 Impala—he reinvented it. Over years of experimentation, he developed a one-of-a-kind 3D paint process that makes the entire body look engraved in intricate patterns, almost like a fully chromed sculpture. The result? A mind-blowing, reflective finish that turns heads everywhere it goes.

If there’s one thing about Joe Ray’s Lincoln Continental Mark V, it’s that it never stays the same. Since he first bought it new in 1979, it’s gone through four major transformations, each time getting bolder, flashier, and more over-the-top. But in its latest (and supposedly final) form, now known as “Las Vegas”, Ray went all in on the theme—and it paid off.

This lowrider is a full-on tribute to casino culture, inside and out. The interior is packed with hot-pink velour, poker chips, gold-plated details, and actual gaming tables. There’s a craps table built into a door panel, a roulette wheel as a tire cover, and even antique slot machines tucked into the trunk. The dashboard? It’s a Blackjack table, complete with the classic “Dealer must draw to 16 and stand on all 17s” rule stamped across it. Every detail is a nod to the glitz and excess of Vegas itself.

Every pinstripe, every airbrushed design, every chrome detail told a story.

These cars weren’t just for show. They were symbols of resilience, creativity, and cultural pride. the margins.

The Zoot Suit in Modern Fashion: A Revival of Identity

To see these suits on a Los Angeles runway in 2025 is to witness something powerful: proof that the zoot suit never died—it evolved.

The pachuco and pachuca aesthetic is more than just vintage nostalgia. It is an act of reclamation, a visual statement that says, “We are still here, and we are still proud.” For decades, mainstream America tried to bury the zoot suit, associating it with delinquency, criminality, and subversion. But the very thing that made it dangerous to the establishment—its boldness, its defiance, its refusal to conform—is exactly why it has endured.

Today, the zoot suit’s influence ripples across the fashion industry, from high-fashion runways to retro-inspired streetwear. Designers have borrowed from its bold proportions, exaggerated shoulders, and wide-legged trousers, modernizing them while keeping the spirit of defiance alive.

Celebrities and Artists Have Reignited Interest in the Zoot Suit:

- Music videos and performances continue to pay homage to the pachuco era, from the swagger of swing-inspired artists to Chicano rappers keeping the aesthetic alive in modern-day storytelling.

- Vintage fashion movements have embraced the zoot suit’s aesthetic and cultural significance, blending its elements into contemporary street fashion, tailored menswear, and gender-fluid designs that break boundaries just as pachucos did in the 1940s.

- Movies, television, and even social media have helped reintroduce the world to what it means to be pachuco and pachuca today. Films like Zoot Suit (1981) ignited a cultural revival decades ago, and recent interest in Chicano fashion, history, and resistance movements has kept the zoot suit’s story alive for new generations.

More Than Just Fashion: A Political Statement

The return of the zoot suit is more than a trend—it’s a political statement.

When young Mexican American men and women proudly wear custom-tailored, sharply creased zoot suits today, they are tapping into the same power that terrified the establishment in 1943 during the Zoot Suit Riots. Back then, wearing a zoot suit was an act of rebellion—a refusal to assimilate, a refusal to shrink, a refusal to be invisible.

That same energy exists today. In an era where Mexican Americans and immigrants continue to be scapegoated and villainized, reclaiming our history through fashion is an act of defiance. The zoot suit isn’t just about looking good—it’s about owning space, demanding respect, and reminding the world that we have always been here and always will be.

From the streets of East LA to global fashion houses, from lowrider car shows to Hollywood red carpets, the zoot suit has never faded—it has transformed, adapted, and thrived.

This is not a relic of the past—it is a future we are still building.

Why This Moment Matters: Representation and Resistance in 2025

There’s something deeply powerful about an event like this happening now, in this political climate.

We live in a time where Mexican Americans and immigrants are constantly under attack—where politicians like Donald Trump scapegoat our communities while conveniently ignoring how much we contribute to this country.

But nights like this? They prove that we are still here, still thriving, still making an impact.

The zoot suit and lowrider cultures were born from resistance—from young people who refused to be invisible, who embraced their heritage instead of assimilating. That same defiance is just as necessary today as it was in 1943, during the Zoot Suit Riots.

It’s why seeing Mexican Americans take up space in a museum dedicated to American automotive history is significant. It’s our history too.

And it’s why seeing young people—our next generation—walk proudly in zoot suits is a revolution in itself.

- Our culture is not a relic. It’s not a costume. It’s a living, breathing force that continues to shape Los Angeles and beyond.

- Because the truth is simple: Without Mexican Americans, without Black Americans, without immigrants, there is no America.

Aquí estamos.

Final Thanks and Acknowledgments

This night would not have been possible without:

- The Petersen Automotive Museum, for recognizing the importance of our history and allowing us media access to cover this incredible event.

- Vanessa Estrella and El Pachuco Zoot Suits, for keeping the legacy of the zoot suit alive and continuing to push for representation in fashion.

- All the models, musicians, and attendees, who brought this culture to life and proved that the pachuco legacy is still thriving.

Leave a Reply